The target is a famous journalist who ranked among the foremost English language polemicists of his era; the assailant is something of a lesser luminary, sadly afflicted with a prose style that comes across like a deliberate parody of an obscure 1970s French structural-functionalist political sociology text.

The target is a famous journalist who ranked among the foremost English language polemicists of his era; the assailant is something of a lesser luminary, sadly afflicted with a prose style that comes across like a deliberate parody of an obscure 1970s French structural-functionalist political sociology text.

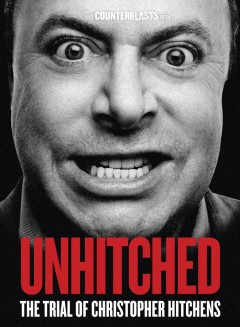

On the literary level, I guess, Richard Seymour’s Trial of Christopher Hitchens was never going to persuade a jury. But the political underpinnings of the charge sheet deserve fairer consideration than they have had in any of the reviews of this book I have read so far, mostly penned by people who obviously haven’t bothered to read the volume they so readily dismiss. I am going to be as charitable as I can.

Hitchens – alongside Paul Foot and John Pilger – was one of a trio of heroes to a generation of leftwing journalists, myself included.

But while Pilger still dedicates himself to making Chomskyite ideas accessible on magazine pages, and Foot rests close to Karl Marx in Highgate Cemetery with his revolutionary socialist credentials still intact, the Hitch switched sides.

It is probably unfair to rank him alongside the many who have made the journey from youthful radicalism to reactionary maturity; he remained identifiably some sort of leftist on many issues until his death in December 2011.

But on the defining issue of his final decade, he was without any doubt on the wrong side, lining up with George W Bush and his team of neoconservative advisors in making the case for the misconceived US-led adventure in Iraq.

Of course there were excellent leftist reasons for wishing to see the fall of Saddam Hussein, and Hitchens’ articles made full use of them. But he didn’t stop there, buying into the ‘al Qa’eda link’ and ‘weapons of mass destruction’ bullshit in supremely credulous fashion.

The sad net result was a failed attempt to prettify the Bush administration’s seizure of a key strategic position in a region where most of the world’s oil is located, rewarding his campaign contributors with lucrative contracts and diverting the electorate’s attention from his mishandling of the economy and the environment in the process.

And in so doing, he waged a personal war on the Anglophone left, denouncing many of his former comrades and lifelong friends with a ferocity and a finesse that sticks in the memory even a decade later.

Such was Hitchens’ stature that it is surely worth a short book to inquire as to why he did so, and Seymour makes a reasonable stab at the project. The trouble is, effectively to stick the boot into a writer of Hitchens’ ability requires a panache that is ultimately beyond the author’s ability to muster.

Much in the manner of a good postgrad student, Seymour has obviously done his homework. This volume is well researched, and he clearly did not shrink from reading as much of Hitchens’ prodigious output as he could place his hands on.

Some of the points he makes are demonstrably correct. He is right, for instance, to highlight a certain strain of imperialist nostalgia in Hitchens’ discussions of literature.

Moreover, Hitchens was indeed ‘a poor atheist’, as Seymour contends, in the sense of demonstrating little awareness of modern theology. For all Hitchens’ professed Marxist materialism, his famous attack on religion in God is Not Great was very much an idealist critique.

As a former fan boy, I was sorry to see where the Hitch ended up, and I entirely understand why Seymour – currently embroiled in the factional turmoil engulfing the Socialist Workers’ Party, incidentally – was moved to chart his progress.

Despite the universal panning that ‘Unhitched’ seems to have come in for everywhere else, it remains a worthwhile read for anyone with an interest in the subject.